Book Returns—Insanity Incarnate

Yesterday I mentioned two things in my discussion of royalty statements that I wanted to talk a bit more about today. One was returns:

Returns are a crucial part of the current book publishing model; and are one of the reasons it’s collapsing in on itself. Back during the Great Depression, book publishers started making books returnable. If a retailer had the book on his shelves for at least six months, and no longer than eighteen months, he could return it for full credit. This encouraged bookstores to buy more inventory than they might otherwise, since they couldn’t lose money if it didn’t sell. Some time later, the time constraint got removed, so any copy of a book sold to any store, anywhere could be returned to the retailer for full credit.

By the way, books aren’t actually returned to the publisher. Retailers and distributors strip the covers off the books and send them back for credit. The coverless guts are discarded, filling landfills. The pulp paper in paperbacks is so low in fiber it can’t be recycled. Because of this practice, for every physical book sold in the United States, two are printed.

The second thing I mentioned was Bookscan. Bookscan is a service which tracks sales of books selling out of retail stores. Royalty reports track books selling into retail stores. Because books can be returned for full credit, every book going into a bookstore may not be going back out again. Bookscan allows publishers to track books that won’t be returned.

As you can imagine, once the returns policy was put into place, publishers had a problem. They report their sales (shipments to retailers) every six months. But a book can come back at any time, and they’d have overpaid the author. In order to make sure that didn’t happen, they instituted a practice called “reserves against returns.”

Reserves against returns is a practice which more closely resembles alchemy than any sort of business practice. I say this because there is no consistent formula applied to when reserves will be held, when they will be released, or what the percentage will be. For example: Rogue Squadron sells the most copies of any of the X-wing books, and the reserve percentage is 43%. Going down the line, the percentages are 54%, 54% and 47%. Clearly the sheer volume of books in the market doesn’t govern the percentage, since Rogue Squadron has many more copies out there than The Bacta War, and Wedge’s Gamble has more than either of the books that follow it.

By way of contrast, the DragonCrown War books, which sell a tenth of the numbers the X-wing books normally do, have reserves ranging from 15-30%. In a world where books can be returned, one would assume that books with a higher profile (i.e. Star Wars®) would be returned at a much slower rate than other books. One would expect, then, to see those percentages flipped.

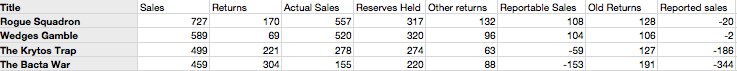

Here’s the even more curious thing with the current reporting on the X-wing books. In the report (and these numbers are cobbled together from two separate sheets) returns get accounted for in three separate areas. I’ll use a chart, and I apologize for having to shrink it down a bit.

From the left, we have:

Sales, which is the number of copies of the $7.99 edition of the book that went out to stores.

Returns indicates the number of the books that came back from stores.

Actual Sales is the difference between these numbers.

Reserves Held is the number of books that Bantam is anticipating will be returned.

Other returns are copies of the same books that have come back from elsewhere, like Canada, New Zealand and other places.

Reportable Sales is the difference between Actual Sales and Reserves Held and Other returns.

Old Returns is old books (more on that in a second).

Reported Sales are the numbers that show up on summary sheet.

The reserves against returns account for over half the number of books known to have been shipped, which is kind of crazy. This is especially insane when we know that publishers have access to the Bookscan numbers and know how many of those books have actually sold. (I seem to recall that Bookscan covers about 75% of the book sales in the USA, which gives the publishers a basis to work from.)

Reserves do get “released” at some point, so the author will get paid for those sales. But there is no set schedule for when they will be released, or what percentage of them will get released. It is entirely possible (even probable) that an author whose book is purchased in January, won’t get paid for that sale for fifteen months or more.

The completely, off-the-wall returns are the ones I have labeled Old Returns. These are a significant problem for two reasons. First, these are the books that were sold at a lower price than the current edition: $6.99 or $5.99. They’re being swapped, one-for-one, for books that cost $7.99. Since authors get paid a royalty based on the cover price of a book, authors losing money on each of these swaps. (If they totaled the royalty earned on those books, and deducted it from the total an author was owed, we’d have an equitable situation; but in a unit-for-unit swap, authors lose credit for that extra dollar.)

Second and even more nuts is the fact that the $6.99 edition of these books stopped being printed by, at the very least, 2009. This means stores are returning merchandise which is over two years old. In the case of $5.99 books coming back, even older. Allowing these legacy returns a ridiculous business practice and the nice thing about the rise of digital sales is that reserves against returns will go away.

So why would a book company jack up the reserve against return rate when, by using Bookscan, they know how many books they’ve sold and simple math will tell them how many could possibly be coming back? Well, aside from older “legacy” copies coming back; could be they’re doing what the bookstores do. The royalty sheets show that the vast majority of returns come in December. Why? Because bookstores strip and return old copies to get them off their inventory. They use the returns policy to balance their books, making the bottom line look better for the end of quarter and end of year reports.

In the case of publishers, with three months of hindsight to use when calculating the reserves, chances are very good that publishers are insulating themselves from the Borders bankruptcy. This despite the fact that via Bookscan numbers and their shipping numbers, they should be able to calculate to the penny what their exposure is. In addition to that, if they raise their reserves, they delay paying out cash. This means they have more money on the books which makes them look great in the quarterly and year-end reports. So, just like the bookstores, they could be using the reserve rate to balance their books on the backs of authors.

Luckily for writers, digital publishing will take care of a lot of this nonsense. It won’t, however, take care of all of it. Why not?

Well, as you’ll see in my next installment here, when it comes to ebook sales there are some seriously odd numbers being reported by traditional publishers. I’ll explain why they’re odd next time, and even show you what you can do to help authors figure out what’s really going on.

Writing up this series of blog posts is cutting into my fiction writing time. If you’re finding these posts useful, and haven’t yet gotten yet snagged my latest novels, please consider purchasing a book. Nice thing about the new age of publishing is that you become a Patron of the Arts, letting writers know what you’d like to see more of simply by voting with a credit card. (Authors charge less when they sell direct, so you save, we make more, and that frees us to write more.)

My latest paper novel, At The Queen’s Command, is available at book retailers everywhere.

My digital original novel, In Hero Years… I’m Dead is available for the Kindle and in the epub format for all the other readers, including the Nook, iPhone, iPod Touch and iPad.

12. Apr, 2011

12. Apr, 2011

9 Responses to “Book Returns—Insanity Incarnate”