High Intensity Writing Workout No. 3

This exercise harkens back to what we covered in High Intensity Writing Workout No. 1. You’ll be using some of the skills you developed there to get through this workout.

One “problem area” (to keep the workout metaphor working) for most writers early on in their careers involves tunnel vision. Whether working from notes or an outline, they focus in on the factoid they need to get across, and stay locked in on it no matter what else might come up.

For example, the outline says that Cliff and Sally are on a second date, and it’s supposed to go horrendously badly. Cliff really wants to get Sally to try out some cool favor of ice cream at some chain place. He insists. Sally gets stiffer and colder, then reminds him that not only has he forgotten that she’s lactose intolerant, but she’s gluten-free and, on top of that, she hates multi-national chains. She even had “buy local” as an interest of hers on Tinder, where they met, for crying out loud. He doesn’t listen to her, and she hated putting up with that stuff with her ex, and she’s not about to do that now with him.

Okay, pure disaster. Worse than a disaster. This is a dating atrocity. And, the fact is, I’m fairly certain, if the writer does that scene any justice, Cliff and Sally ain’t having a third date. In fact, they’re both going home and destroying any evidence of a first and second date.

But, if we back up a little bit, and are flexible, other aspects of the characters might open up. And by “other aspects,” I mean things that the writer may not have even guessed about the characters.

Thus, Cliff and Sally are walking along and he sees the ice cream place. He looks longingly. She notices and asks what’s the matter. He explains that co-workers had raved about the flavor of the month and he’d forgotten about it until just that moment. Then he quickly adds, “But I know you don’t do ice cream, and wouldn’t be caught dead in there, so it’s cool.”

(At this point, we’re off script as far as the outline is concerned. Beyond this point, for some writers, all that exists are dragons…)

Sally looks up at him, slipping her hand through the crook of his elbow. “It’s okay. You can have ice cream. I’m not the diet police.”

“No, look, it’s important to me, since we’re out together, that we do things together. I don’t think you want to sit and watch me eat ice cream.”

“I can think of better things to do, true.” She smiled. “But I’m getting the impression that ice cream is kind of important to you.”

Cliff sighs. “Okay, promise me you won’t hate me or anything, right?”

“I promise.”

“Okay.” He exhaled slowly. “When I was a kid I played Little League Baseball. We weren’t the Bad News Bears, we were the Morbidity and Mortality Newsletter Bears. We couldn’t have won if Ebola wiped out the rest of the league. We practiced with a tee, and most of us struck out.”

“You were bad. Got it.”

“But my grandfather, after every game, he would load us all up in this old van and take us out for soft-serve. And when we finally did win a game—it got called on account of a tornado, so we only won by an Act of God—we got Sundaes.” Cliff gave her a sheepish grin. “Other folks drown their sorrows in beer, celebrate with Champagne. For me it’s a cone, or something with sprinkles.”

Sally glanced down for a moment, then nodded toward the ice cream store. “So, being out with me, cone or sprinkles?”

The first of the two things you’ll want to notice here is that we didn’t make the date a disaster. Frankly, disasters are easy to manufacture. Having Cliff and Sally get closer means that any disaster will be something the readers feel more acutely. It’s the difference between readers thinking Cliff is going reveal himself to be an insensitive clod and fearing he’ll reveal himself to be an insensitive clod. In this latter case, the readers are invested in him, and in seeing the two of them get together, which is what you want.

The second thing is this: the conversation appears to be about ice cream, but it’s really not. Cliff is revealing a vulnerability. You can imagine, from the above, that his childhood wasn’t perfect. His grandfather appears to be his custodial parent, he drives an old van so they likely didn’t have much money, and Cliff hung out and played with lots of kids who were losers (at sports, anyway). Just in that story about Little League you’ve hinted at tons of things which can later get worked back into the story, like having teammates—no longer losers—show back up in his life when he most needs the support.

Writing and developing a story is a cyclical process. You develop what you can, then start writing. What you write will expand on or subtract from or completely alter bits and pieces stuff you developed. You make changes, account for the consequences of those changes, and keep writing. The cycle starts again.

The cool thing is that when you allow for the story to change and find a path which is true and interesting for the characters, it will be more interesting for you and for the reader. This sort of organic development adds a lot of energy and depth to stories.

The Workout:

I want you to find/make up some random bits of dialogue. Eavesdrop on a conversation at a coffee shop, pull a line from a book or a movie (or Cliff and Sally’s conversation), or yank something from a news story. You can start with one or two, but probably need to follow this exercise through a half-dozen to get where the idea is comfortable.

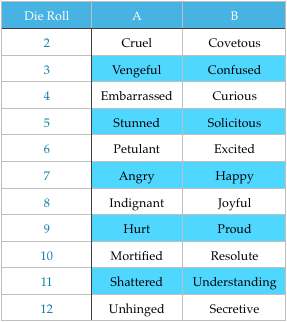

The chart to the left is a remnant of my game designer training. You can pick an emotion/aspect off it, or roll two six-sided dice to generate a result. You can choose which column, A or B, you want to start with, but if you roll doubles (same result on both dice) you switch. Whatever descriptor you get, you use to characterize the sentence with an attribution tag.

Let’s say our sentence is “I really wanted chocolate ice cream.” I roll the dice and come up with angry. So I write:

Cliff pounded his fist into the wall. “I really wanted chocolate ice cream.”

From there, you run the dialogue for another 5-6 lines, hitting a back and forth exchange. For each new line, you roll the dice and characterize the new line with that emotion. In this case I roll an 8 and get “Indignant.”

Sally lifted her chin. “That is chocolate. From Ice Castle. A month ago you said that was the best chocolate ice cream you’d ever had.”

“It is?” Blood drained from his face. He stared at the spoon and the half-melted glob on it. “But it doesn’t taste like chocolate. Not even close.”

Her expression froze. “I can smell the chocolate from here, and a woman at the store, she tasted a sample and said it was better than sex.”

Cliff sat down hard, the spoon clattering in the bowl. “What’s wrong with me? I haven’t had a problem like this since…” He swallowed hard. “Oh my God, they didn’t get all of the tumor.”

(The random roll results after Indignant were: mortification, stunned and stunned.)

While this example went dark fast, if we’d started on the happy track, or maybe with something on the top or bottom of the chart, we’d have been off into entirely different territory. Regardless, until I got those dice rolls, I didn’t know poor Cliff had had a brain tumor. Or someone could have been working black magick on him, or an Alien larva could have been eating its way through his brain or…. But, having discovered that fact, now I deal with it.

Once you’ve run five lines, start with another emotion and see where that conversation goes. You may only need to do it twice per sentence to get the idea, but four times ought to really let you master the concept.

So, go ahead and give the exercise a try. And keep that chart handy. If you’re working on a story, a random roll of some dice might get you thinking in new directions. Just having someone react angrily to something that shouldn’t make anyone angry will get the juices flowing. Better yet, when you think you’ve written yourself into a corner, a shift like this will show you there’s a lot more possibilities out there.

©2015 Michael A. Stackpole

________________________

If you’re serious about your writing, you’ll want to take a look at my book, 21 Days to a Novel. It’s a 21 day long program that will help you do all the prep work you need to be able to get from start to finish on your novel. If you’ve ever started a book or story and had it die after ten pages or ten chapters, the 21 Days to a Novel program will get you past the problems that killed your work. 21 Days to a Novel covers everything from characterization to plotting, showing you how to put together a story that truly works.

25. Feb, 2015

25. Feb, 2015

Comments are closed.